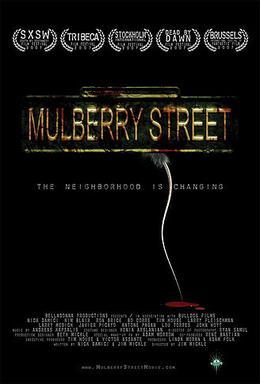

Mulberry Street (2006)

Rated R for creature violence/gore and language

Score: 4 out of 5

Mulberry Street, written and directed by Jim Mickle and Nick Damici (who also made the great Stake Land four years later), may just be the most New York zombie movie ever made. The zombie plague is spread by rats, an issue with which anybody from the Big Apple can sympathize, and furthermore, the zombies take on rat-like features -- their ears turn pointed and have tufts of hair sprouting out of them, they grow long incisors for nibbling, and instead of moaning, they squeak and squeal. The characters all felt like not just real people, but more specifically, like real working-class New Yorkers, and furthermore, the film spends its slow-burn first act letting us get to know them and their struggle to hold onto their apartment from all-too-human forces while the zombie outbreak spreads in the background. And that leads to the final piece of the puzzle, which is the fact that, underneath the rat-zombie mayhem, it's fundamentally a film about the changes that were digging their claws into New York and other major American cities in the 2000s and beyond. Its tiny budget may show in many places, but it's still a highly enjoyable little B-movie that's bound to wriggle its way into the nightmares of any musophobes who watch it.

Our protagonists are a group of people who live in a small apartment building on Mulberry Street in Manhattan. Clutch is a retired boxer whose soldier daughter Casey is returning home from Iraq, Kay is a Polish immigrant, single mother, and bartender raising her teenage son Otto, Charlie and Frank are elderly brothers (the former a World War II veteran), Coco is a gay black guy, and Ross is the super. All of them are facing eviction, with a property developer having bought their apartment and seeking to renovate it for a more upper-class clientele. And here is where we get the main thrust of what the film is really about. The zombie genre is one that is known for social commentary thanks to George A. Romero's lasting influence, the zombies often standing in for and used to discuss a greater issue like consumerism (in Dawn of the Dead), globalization (in the novel World War Z), the military-industrial complex (in The Crazies and the Dead Rising games), or the post-Vietnam tension between soldiers and civilians (in Day of the Dead). And in this film, the zombies represent gentrification. It's only in the second act when this really starts to turn into a horror film; until then, outside of a few scenes establishing the coming threat, it's a film about a group of blue-collar Joes and Janes who are trying to get on with their lives yet finding that their old streets are slowly turning unrecognizable. A brand-new apartment tower has just gone up down the street. Their old watering hole is now filled with yuppies. The wealthy family in their building flees the moment things start going to hell, the fact that they have a car meaning that they can still leave Manhattan after the trains are shut down (or so they think); it seems that they got scared off by the city's infamous rats. The rat zombies are just the final blow sweeping them out of the city they once called home, literally bashing down the doors of the apartment they've been struggling to hold onto for years, and the fact that so much care went into realizing them and their struggles meant that I was feeling their pain even before they were hunkered down for the big siege. When this film came out in 2006, the gentrification of the Bloomberg years was in full swing, Manhattan becoming just about unaffordable for anybody who didn't make fifty thousand dollars a year, and the Great Recession that followed only slowed things down briefly. Nowadays, the idea of any working-class people living anywhere in Manhattan south of Harlem is considered a fantasy, and Harlem too is on the same path, as are Brooklyn and even parts of the South Bronx.

The fact that the world these characters live in felt as gritty and real as it did also helped sell me on the authenticity of it. While the film's tiny budget (about $60,000) meant that it had to cut a lot of corners on things like special effects and actors (co-writer Nick Damici also plays the protagonist Clutch, and he enlisted his dad to play Charlie), it also makes it feel truly raw, like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, The Blair Witch Project, and any number of old grindhouse flicks. It's a testament to Jim Mickle's talent behind the camera that this film did not feel as low-budget as it actually was, using real New York locations as settings and employing darkness and camerawork to hide the special effects without rendering scenes incomprehensible. The action, be it in a bar, out on the streets, or in the apartment where most of it takes place, was intense, mainly by keeping the zombies lurking in the shadows or just off-screen yet constantly squeaking and scratching. (Something tells me that they were merely dramatizing their own experiences with rats in that regard.) The acting is rough, but it never feels like the cast was unenthused, and all of them felt like distinct characters who were attached to their city and their home. During the scene where Frank was incredulously describing to Charlie how the super had "turned into a big fuckin' rat" (Ross gets bit early on, so it's not a spoiler), it sounded like exactly what I'd imagine coming from the mouth of an actual New Yorker (like some of my family members and their friends) in the middle of a zombie apocalypse, and variations on that conversation kept putting smiles on my face.

Our protagonists are a group of people who live in a small apartment building on Mulberry Street in Manhattan. Clutch is a retired boxer whose soldier daughter Casey is returning home from Iraq, Kay is a Polish immigrant, single mother, and bartender raising her teenage son Otto, Charlie and Frank are elderly brothers (the former a World War II veteran), Coco is a gay black guy, and Ross is the super. All of them are facing eviction, with a property developer having bought their apartment and seeking to renovate it for a more upper-class clientele. And here is where we get the main thrust of what the film is really about. The zombie genre is one that is known for social commentary thanks to George A. Romero's lasting influence, the zombies often standing in for and used to discuss a greater issue like consumerism (in Dawn of the Dead), globalization (in the novel World War Z), the military-industrial complex (in The Crazies and the Dead Rising games), or the post-Vietnam tension between soldiers and civilians (in Day of the Dead). And in this film, the zombies represent gentrification. It's only in the second act when this really starts to turn into a horror film; until then, outside of a few scenes establishing the coming threat, it's a film about a group of blue-collar Joes and Janes who are trying to get on with their lives yet finding that their old streets are slowly turning unrecognizable. A brand-new apartment tower has just gone up down the street. Their old watering hole is now filled with yuppies. The wealthy family in their building flees the moment things start going to hell, the fact that they have a car meaning that they can still leave Manhattan after the trains are shut down (or so they think); it seems that they got scared off by the city's infamous rats. The rat zombies are just the final blow sweeping them out of the city they once called home, literally bashing down the doors of the apartment they've been struggling to hold onto for years, and the fact that so much care went into realizing them and their struggles meant that I was feeling their pain even before they were hunkered down for the big siege. When this film came out in 2006, the gentrification of the Bloomberg years was in full swing, Manhattan becoming just about unaffordable for anybody who didn't make fifty thousand dollars a year, and the Great Recession that followed only slowed things down briefly. Nowadays, the idea of any working-class people living anywhere in Manhattan south of Harlem is considered a fantasy, and Harlem too is on the same path, as are Brooklyn and even parts of the South Bronx.

The fact that the world these characters live in felt as gritty and real as it did also helped sell me on the authenticity of it. While the film's tiny budget (about $60,000) meant that it had to cut a lot of corners on things like special effects and actors (co-writer Nick Damici also plays the protagonist Clutch, and he enlisted his dad to play Charlie), it also makes it feel truly raw, like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, The Blair Witch Project, and any number of old grindhouse flicks. It's a testament to Jim Mickle's talent behind the camera that this film did not feel as low-budget as it actually was, using real New York locations as settings and employing darkness and camerawork to hide the special effects without rendering scenes incomprehensible. The action, be it in a bar, out on the streets, or in the apartment where most of it takes place, was intense, mainly by keeping the zombies lurking in the shadows or just off-screen yet constantly squeaking and scratching. (Something tells me that they were merely dramatizing their own experiences with rats in that regard.) The acting is rough, but it never feels like the cast was unenthused, and all of them felt like distinct characters who were attached to their city and their home. During the scene where Frank was incredulously describing to Charlie how the super had "turned into a big fuckin' rat" (Ross gets bit early on, so it's not a spoiler), it sounded like exactly what I'd imagine coming from the mouth of an actual New Yorker (like some of my family members and their friends) in the middle of a zombie apocalypse, and variations on that conversation kept putting smiles on my face.

The Bottom Line:

This is a grimy B-movie that runs on equal parts inspiration and perspiration, its solid frights and authentic characters wrapped around a conscious core that's all the more relevant today. If you're willing to overlook its tiny budget and don't care that it's slow going in the beginning, you will certainly enjoy this.

No comments:

Post a Comment