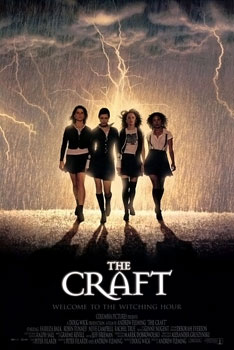

The Craft (1995)

Rated R for some terror and violence, and for brief language

Score: 4 out of 5

The Craft, having premiered less than a year before Scream, feels like kind of an odd duck amidst the '90s teen horror landscape. It doesn't even try to engage in the self-referential humor that Scream popularized, with little in the way of snide nods to other movies about witches that are followed up with a "no, this is how witchcraft actually works", even though a big part of the film's appeal, then and now, was that the filmmakers drew on actual, real-life Wiccan practices for their portrayal of such. It's as stylish and pop-culture-minded as its contemporaries later in the decade, but it's also countercultural and subversive in ways that go beyond just the fact that the main characters wear lots of black. It's a film that's carbon-dated to the '90s in some ways yet feels just as relevant now. It's hardly a perfect film, but it's one where I can see how it stood the test of time and became a cult classic among what is coming on three generations of young horror fans (women especially, if the Popcorn Frights screening I just saw this at was any indication), despite a mixed critical reception and only modest box-office success at the time. In many ways, it reminded me of a gender-flipped version of The Lost Boys, another film that crafted a stylish horror movie out of a different decade's punk/goth counterculture, making up what it lacked in pure frights with sex appeal, visual flair, and some sharp-dressed villains.

Said villains are Nancy, Bonnie, and Rochelle, a trio of teenage girls at a Catholic high school in Los Angeles who dabble in witchcraft but haven't been able to actually accomplish anything. What they're missing is a "natural" witch, one who is gifted on her own, in order to complete their circle and acquire real power. They find such in Sarah, a new girl who just moved to town from San Francisco and seems to have some strange supernatural powers. Upon inviting her into their coven, the girls acquire power beyond their wildest dreams, using it to reshape their lives and get revenge on people they hate. Unfortunately, these girls have no idea just what kind of power they're playing around with, and once people start dying, Sarah realizes that her new friends, Nancy especially, are turning into the Wicked Witches of the West Coast.

I remember the YouTuber Lindsay Ellis having once done an episode of her old show The Nostalgia Chick on this film, in which she concluded that, at the end of the day, they later remade it as a non-supernatural teen comedy titled Mean Girls and wound up with a better film all around. I will not dispute her argument that Mean Girls, a comedy classic of the 2000s, is a better film than The Craft, but I would like to add that the comparison doesn't exactly hurt this film, either. In fact, going into it as a supernatural horror version of Mean Girls is perhaps the best possible way to enjoy it, as it is, above all else, a film about a war between two young women, one a vanilla heroine for the audience to project themselves upon and the other a campy, over-the-top villain who is far and away the most interesting character in this. Fairuza Balk will always be forever known as Nancy Downs, diving so deep into the role and having so much fun doing so that, for the longest time, people thought that Balk was a Wiccan in real life -- because there's no way she could've been that good, right? (The rumor started from the fact that she did own a magic shop at the time. She actually bought it from a friend of hers who wanted to retire, partly as a favor and partly to research her role in this film; in other words, not an actual witch if she had to study witchcraft first.) Balk was clearly having the absolute time of her life playing the kind of bad guy that young actresses don't normally get to play outside of voice roles in Disney movies, a ferocious wee-atch (hi there, The Covenant, you awful gender-flipped pseudo-remake you!) who uses her newfound magical powers to get what she wants by hook or by crook without concern for others. Even though the other characters were kind of flat and existed largely to react to her actions, I barely cared because Balk was just that good at conveying this thoroughly amoral shitheel who immediately lets power go to her head, stealing the show in every scene she was in.

That said, we have to get to the other girls at some point. None of them are near as memorable as Nancy, whether it be through thin writing or a flat performance. Neve Campbell's Bonnie is the ugly duckling, a girl who was left disfigured by a fire that covered her back in burn scars, and uses her power to become a swan who quickly transitions into a vain, selfish bimbo (in other words, a swan). Rachel True's Rochelle, meanwhile, is one of the only black students at the Catholic school the protagonists attend, and is ruthlessly bullied on account of it by Christine Taylor's blonde Fox News host in training Laura Lizzie. The problem with both of them is that these are their only real character traits, with a fair bit of both characters' development having been left on the cutting room floor. Again, to go back to Mean Girls, in that film Regina's underlings Gretchen and Karen were well-developed characters in their own right who existed independently of her, and while the deleted scenes offer Bonnie and Rochelle more depth and nuance (Rochelle's parents are extremely controlling, the both of them stick with Nancy because they're afraid of losing their powers and going back to being losers), there isn't a director's cut for me to watch here. The biggest fault, however, comes with Sarah. Her only character trait is that she is a "natural" witch whose magic is innate, her personal life relegated to subplots like the love spell she puts on Skeet Ulrich as the hunky classmate she's attracted to (who turns into a stalker). We initially get hints that she moved to Los Angeles for a reason related to her powers, but this never comes up, and her parents are little more than bit parts. This might have been forgivable had Sarah's actress put any energy into the part the way that Campbell and True did with theirs, but Robin Tunney often felt disinterested, reminding me a bit of Kristen Stewart in the Twilight films. She wasn't as bad as, say, Rooney Mara in the Nightmare on Elm Street remake (or Stewart in Twilight, for that matter), but she did little to elevate the part, either. She did what the script demanded of her, and not much else. Also, as a minor aside, her wig was pretty noticeable (she had shaved her head for Empire Records the prior year), and seemed to change color in a couple of scenes -- and not just the famous one where she changes it magically.

It's that scene, however, that symbolizes where the film's real magic (pun very much intended) comes through. A great villain alone wouldn't have made this such an enduring cult classic, not with its other faults. No, this is a film that's quite interested in its subject matter and in treating it with about as much respect as you can realistically demand from a Hollywood teen horror movie. While some obvious artistic license was taken (the god the witches invoke was made up for the movie, for one), the things the main characters do are based less on other horror movies about witchcraft and more on real Wiccan spells and traditions. Magic can be used for evil, but during the climax, Sarah uses it for good as well. It is portrayed as not inherently good or bad, the film being disinterested in differentiating between "dark" and "light" magic; it is a tool, the only rule being that whatever you do will come back around to you threefold. By the end, while the bad guys lose, Sarah does not give up her powers so she can be "normal", instead remaining an extremely powerful witch -- a good witch, but one who still regularly practices witchcraft. It's no wonder, then, that real witches, Wiccans, and pagans have embraced this film even with its inaccuracies, especially given the feeling of wonder that flows through the scenes where the characters are first playing around with their powers. When they first levitate Rochelle using what at first looks to be the old "light as a feather, stiff as a board" trick but turns out to be something more, it is simultaneously sweet and awesome both rolled into one, capturing the feel of a group of young women awakening to something more powerful than themselves and realizing that they can use it for their own ends. The final confrontation between Nancy and Sarah doesn't pack many big scares (unless you don't like bugs or snakes) but does offer up plenty of memorable set pieces, from Sarah's hallucinations to the game of cat-and-mouse that they play to the magic trickery they employ to misdirect each other to some good old-fashioned telekinesis. At the end of the day, The Craft isn't a horror movie so much as it is a changeling fantasy, an edgier, female-driven prototype for Harry Potter wherein witchcraft is an awesome force that can change your life for the better provided that you're not an asshole who goes about abusing your power. In light of this, Sarah being a fairly flat character actually works to the film's benefit; much like Bella Swan in Twilight or (to go right back to that comparison that works so well here) Cady Heron in Mean Girls, her characterization is left open enough that the film's target audience can project their own personalities and motivations onto her as she reacts to all the supernatural goings-on around her.

That said, we have to get to the other girls at some point. None of them are near as memorable as Nancy, whether it be through thin writing or a flat performance. Neve Campbell's Bonnie is the ugly duckling, a girl who was left disfigured by a fire that covered her back in burn scars, and uses her power to become a swan who quickly transitions into a vain, selfish bimbo (in other words, a swan). Rachel True's Rochelle, meanwhile, is one of the only black students at the Catholic school the protagonists attend, and is ruthlessly bullied on account of it by Christine Taylor's blonde Fox News host in training Laura Lizzie. The problem with both of them is that these are their only real character traits, with a fair bit of both characters' development having been left on the cutting room floor. Again, to go back to Mean Girls, in that film Regina's underlings Gretchen and Karen were well-developed characters in their own right who existed independently of her, and while the deleted scenes offer Bonnie and Rochelle more depth and nuance (Rochelle's parents are extremely controlling, the both of them stick with Nancy because they're afraid of losing their powers and going back to being losers), there isn't a director's cut for me to watch here. The biggest fault, however, comes with Sarah. Her only character trait is that she is a "natural" witch whose magic is innate, her personal life relegated to subplots like the love spell she puts on Skeet Ulrich as the hunky classmate she's attracted to (who turns into a stalker). We initially get hints that she moved to Los Angeles for a reason related to her powers, but this never comes up, and her parents are little more than bit parts. This might have been forgivable had Sarah's actress put any energy into the part the way that Campbell and True did with theirs, but Robin Tunney often felt disinterested, reminding me a bit of Kristen Stewart in the Twilight films. She wasn't as bad as, say, Rooney Mara in the Nightmare on Elm Street remake (or Stewart in Twilight, for that matter), but she did little to elevate the part, either. She did what the script demanded of her, and not much else. Also, as a minor aside, her wig was pretty noticeable (she had shaved her head for Empire Records the prior year), and seemed to change color in a couple of scenes -- and not just the famous one where she changes it magically.

It's that scene, however, that symbolizes where the film's real magic (pun very much intended) comes through. A great villain alone wouldn't have made this such an enduring cult classic, not with its other faults. No, this is a film that's quite interested in its subject matter and in treating it with about as much respect as you can realistically demand from a Hollywood teen horror movie. While some obvious artistic license was taken (the god the witches invoke was made up for the movie, for one), the things the main characters do are based less on other horror movies about witchcraft and more on real Wiccan spells and traditions. Magic can be used for evil, but during the climax, Sarah uses it for good as well. It is portrayed as not inherently good or bad, the film being disinterested in differentiating between "dark" and "light" magic; it is a tool, the only rule being that whatever you do will come back around to you threefold. By the end, while the bad guys lose, Sarah does not give up her powers so she can be "normal", instead remaining an extremely powerful witch -- a good witch, but one who still regularly practices witchcraft. It's no wonder, then, that real witches, Wiccans, and pagans have embraced this film even with its inaccuracies, especially given the feeling of wonder that flows through the scenes where the characters are first playing around with their powers. When they first levitate Rochelle using what at first looks to be the old "light as a feather, stiff as a board" trick but turns out to be something more, it is simultaneously sweet and awesome both rolled into one, capturing the feel of a group of young women awakening to something more powerful than themselves and realizing that they can use it for their own ends. The final confrontation between Nancy and Sarah doesn't pack many big scares (unless you don't like bugs or snakes) but does offer up plenty of memorable set pieces, from Sarah's hallucinations to the game of cat-and-mouse that they play to the magic trickery they employ to misdirect each other to some good old-fashioned telekinesis. At the end of the day, The Craft isn't a horror movie so much as it is a changeling fantasy, an edgier, female-driven prototype for Harry Potter wherein witchcraft is an awesome force that can change your life for the better provided that you're not an asshole who goes about abusing your power. In light of this, Sarah being a fairly flat character actually works to the film's benefit; much like Bella Swan in Twilight or (to go right back to that comparison that works so well here) Cady Heron in Mean Girls, her characterization is left open enough that the film's target audience can project their own personalities and motivations onto her as she reacts to all the supernatural goings-on around her.

The Bottom Line

In some ways, The Craft is a campy mess that wears the mid-'90s on its sleeve, but in others... well, it's that, and it's awesome because of it. It's a film where a remake could probably smooth out the jagged edges (in fact, I'd love to see one that just makes the witches the popular girls and leans into all the similarities to Mean Girls), but no matter how good it winds up being, this film's mix of gothic style and a teen power fantasy will resonate for a long time to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment